I just finished reading “The Great Tax Wars” by Steven R. Weisman. From the first income tax during the Civil War through WWI, this book describes the (familiar!) debate about how progressive the tax system should be, and even whether or not we should have an income tax.

I found the themes and arguments in the book to be relevant to our day, though often 160 years old. Yes, the topic is pretty dry, and I did get bogged down in some of the debates, for example about the sixteenth amendment. Instead of any more of a review, in what follows I give a few quotes from the book, each with a bit of context. Though Google Books for some reason does not allow links to all quotes from the book, when allowed such links are provided.

The book starts with the Civil War, including the first use of a mildly progressive income tax by the Union to pay for the war. During debate in Congress, some Republicans supported a progressive tax: “I think it is just, right, and proper that those having a larger amount of income shall pay a larger amount of tax,” declared Representative Augustus Frank, an upstate New York Republican” (p 84). In contrast, the Confederacy resisted using an income tax, and the taxes it imposed were regressive. It seems that the basic idea of taxation was a tough one for the South: “The sorry story of financing the Confederate cause raised the question of whether a government that believed in decentralization and states’ rights could mobilize the resources to prosecute a war. The South was caught in the paradox of its own politics” (p72).

Not all of the book is dry wonkiness. On p 92 we read that soon after Lincoln’s second inagural, he visited Richmond where “word spread of his presence, and soon he was surrounded by throngs of former slaves, shouting, ‘Bless the Lord, Father Abraham’s come.’“

After the war, wealthy interests moved against the income tax: “The income tax is the most odious, vexatious, inquisitorial, and unequal of all our taxes” the New York Tribune said in 1869 (p97). In contrast, Grover Cleveland gave the following provocative quote in a speech to Congress at the end of his first term (p112): “the communism of combined wealth and capital, the outgrowth of overweening cupidity and selfishness, which insidiously undermines the justice and integrity of free institutions, is not less dangerous than the communism of oppressed poverty and toil.“

Citing stats from Thomas Shearman, on p 123 we read “Since 1860, federal taxation had increased sixfold, yet the tax burden was primarily borne by the poor. At the same time, corporate profits had increased tenfold, much of it untaxed. It cost rich Americans 8 to 10 percent of their earnings to finance the government, while the poor paid taxes equivalent to 75 to 80 percent of their savings.”

On p 201, we read a quote from Theodore Roosevelt that sounds like support of a progressive wealth tax: “I feel that we shall ultimately have to consider the adoption of some such scheme as that of a progressive tax on all fortunes, beyond a certain amount“. My guess is that Roosevelt was thinking more of an inheritance tax, rather than a Piketty-style wealth tax.

Roosevelt saw the wealthy as having significant responsibilities (p 202): “One interesting aspect of this message was that Roosevelt was embracing an argument going back to the Civil War: the wealthy man, he said, enjoys unusual protections from government and therefore has “a peculiar obligation to the State because he derives special advantages from the mere existence of government.“

The book covers the debate about the sixteenth amendment, which explicitly allowed an income tax. For whatever reason I have no quotes from this debate, only a quote about the first income tax after the amendment’s passage, from p 278: “On May 8, 1913, the House approved with surprisingly little

controversy the first income tax law that would actually take effect since 1872, when the Civil War era taxes were repealed. … Taxing (only) incomes of more than $4,000 meant that the tax would affect only the wealthiest 3 percent of the population.“

On p 306 Cordell Hull is quoted: “An irrepressible conflict has been raging for a thousand years between the strong and the weak, and the former always trying to heap the chief tax burdens upon the latter. That conflict still continues.“

On p 309 we read about a study conducted around 1916: “One study, by an independent group of academics, union leaders and some business representatives called the Industrial Commission, endorsed the view that labor unrest stemmed form the unequal distribution of American wealth. It cited the fact that forty-four families earned an aggregate income of $55 million, whereas factory and mine workers earned less than $10 a week. Basil M. Manly, the commission’s research director, spoke of the “industrial feudalism” of the Rockefellers, Morgans, Vanderbilts and Astors. He urged an inheritance tax limiting inheritances from any estate to $1 million.” $1M in 1916 is about $30M in 2024.

On p 343, speaking about the 1920s, we read “… the heroes of the decade were to be the business giants lionized as the agents of what looked like permanent prosperity to the American political landscape. Wilson’s New Freedom was all but forgotten. Whereas in 1912 the nation had turned drastically to the left, perhaps without realizing it, eight years later it turned drastically to the right.“

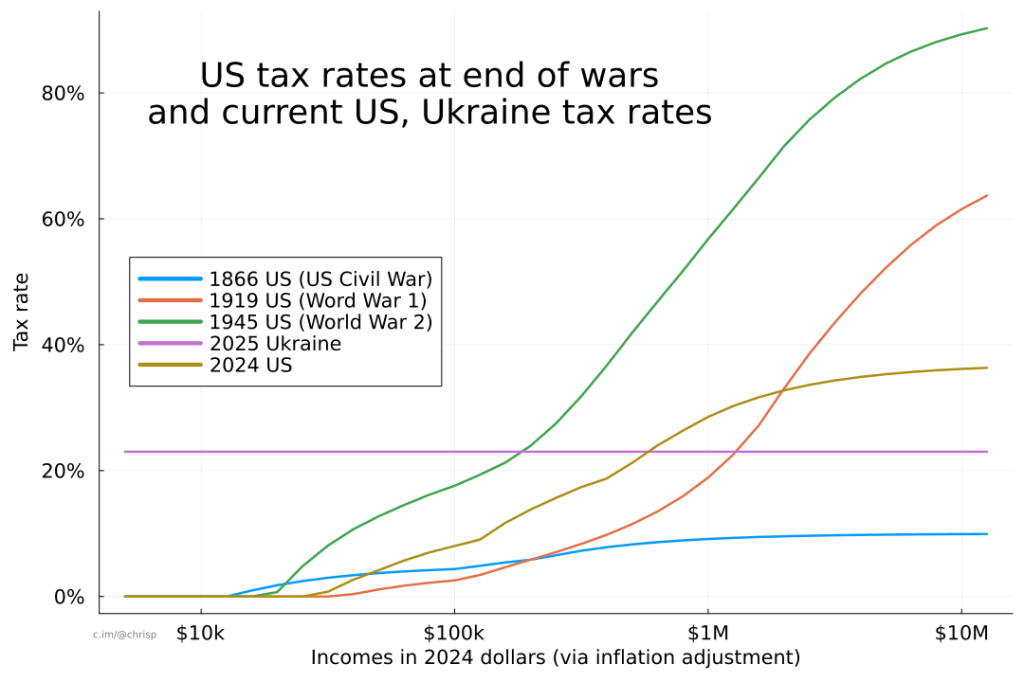

On p 346, speaking about WW1 and the income tax: “… the tax structure would not have occurred without the war. One of the ironies of history was that out of the devastation of civilization as it was known, came the dramatic creation of a vibrant tax and economic system that Americans live with today. Only a war could drive tax rates, even for a tiny minority, from an extremely modest 7 percent at the outset of the conflict to the astounding level of 77 percent on the wealthiest Americans.“

In the Epilogue, the last paragraph of the book reads “A long time has pased since the Civil War, when Representative Justin Morrill compared the enactment of the income tax to Adam and Eve being expelled from their ‘untaxed garden’ and forced to make their solitary way in the world. We may yearn to return to the Garden of Eden, but we have learned that taxes are the price we pay to live in the real world, cope with its dangers and meet the needs of a modern nation. Even to establish Paradise on earth, we will have to pay the way.“

UPDATE: I made minor clarifications on Dec 9 2025.